Bioplotting-Crypts

Overview and technical details of a 3-dimensional bioplotter for production of intestinal crypt organoid models.

Project maintained by daltonjay Hosted on GitHub Pages — Theme by mattgraham

Biological Relevance

The Intestine

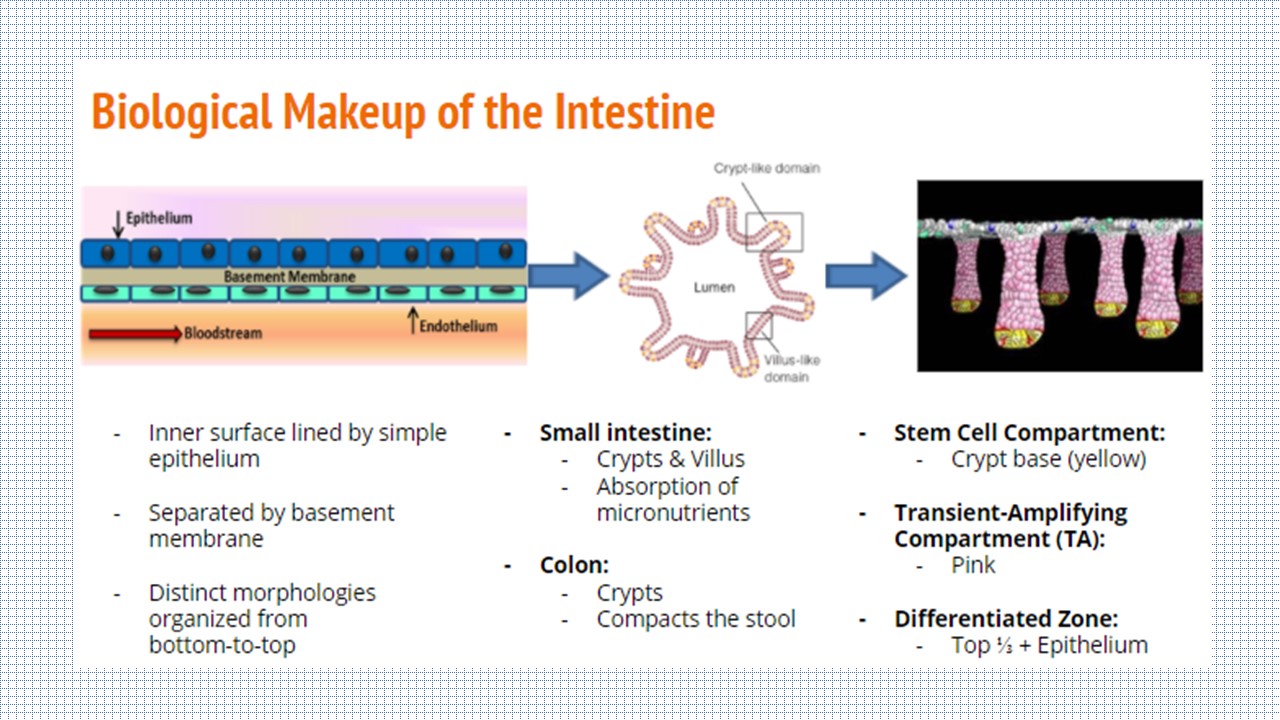

The intestine is divided into two sections: the small intestine and the large intestine, or colon. The inner surface of each is lined by a simple epithelium and endothelium, separated by a basement membrane. While the small intestine epithelium is comprised of crypts and villus structures for the absoprtion of micronutrients, the colon only has crypts on its epithelial surface and primarily functions to compact the stool. Although there are differences between the two sections, the role of the crypt is the same: house the stem cells in the bottom third of the structure so they can differentiate upward towards the lumen.

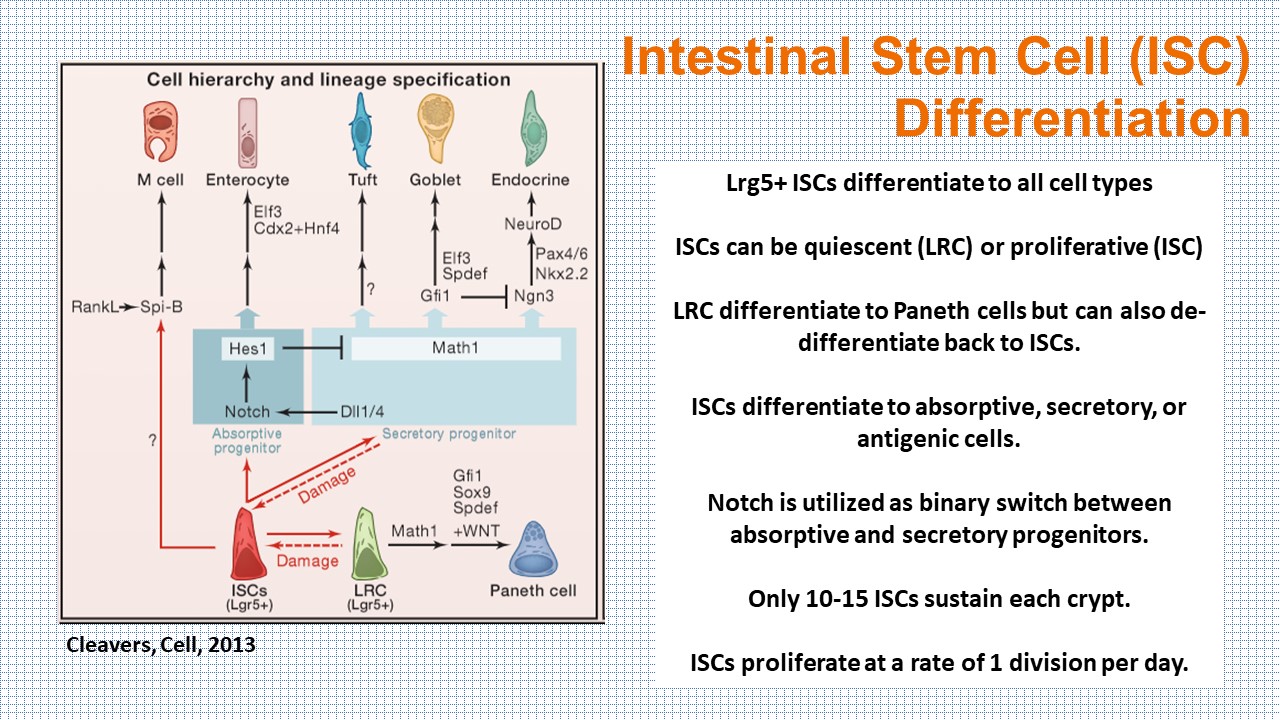

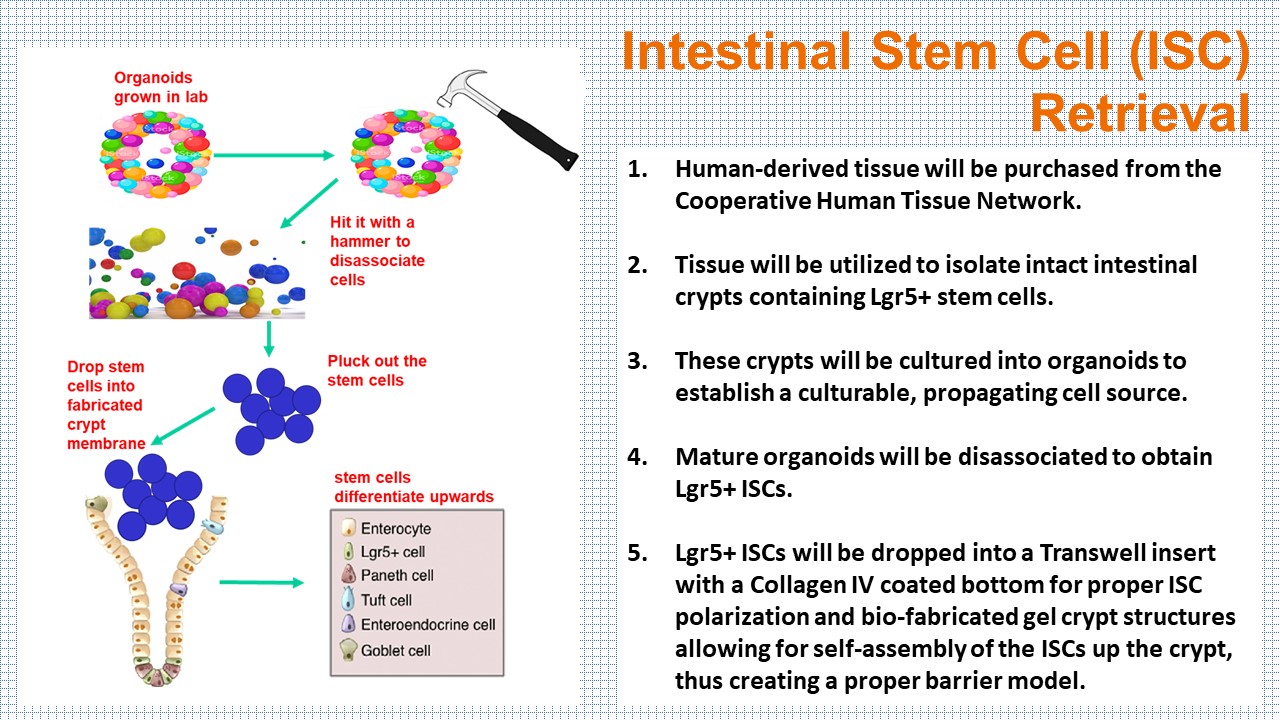

Each of the intestinal cell types are differentiated from the Lgr5+ stem cells in the bottom of the crypt. In the organoid model, the cells can be grown along a crypt-villus axis, with the capability of sampling the cellular milieu directly. However, the organoid model falls short of recapitulating the in vivo physiology and pathology of the human body.

| Epithelial Cell Type | Function | Biomarker |

|---|---|---|

| Enterocyte | Absorption, most abundant | SLC10A2 - Bile Acid Transporter |

| Goblet | Mucus secreting | TFF3 - Trefoil Factor 3 |

| Enteroendocrine | Hormone production | CHGB - Chromogranin B |

| Tuft | Prostanoid production, Pathogen elimination | DCLK1 - Microtubule kinase |

| Paneth | Nurtures ISCs in crypt | DEFA5 - Defensin Alpha 5 |

| M-cell | Antigen transport | GP2 - Glycoprotein 2 |

SnapShot:The Intestine, Cleavers, 2013

SnapShot:The Intestine, Cleavers, 2013

Here we propose to bio-print an architecturally sound crypt structure allowing for luminal accessibility, tissue polarity, cell migration, and cellular responses of in vivo intestinal crypts enabling high-throughput evaluation of the intestinal barrier membrane and mucus production.

Why is this important?

The disruption of the intestinal barrier results in intestinal permeability which facilitates translocation of harmful substances and pathogens to the bloodstream, causing disruption of homeostasis. As such, drug and toxin studies across the intestinal barrier are pertinent to gastrointestinal medicine. Our bio-printed organoid model offers the possibility of recreating a physiologically realistic tissue microenvironment for a breadth of gastrointestinal cells spanning all intestinal cell types.

By bio-fabricating the epithelial surface into a Transwell insert, we are creating an enteroid with an accessible lumen. This is unlike cultured enteroids enclosed in the ECM gel where the lumen is difficult to sample or manipulate without causing physiologically-irrelevant biochemical signals and stimuli.

Potential Applications for Researchers

- Barrier Function

- Drug Testing

- Disease Modeling

- Personalized Medicine

Study Models

Existing approaches for studying biological systems have focused largely on either whole organism studies or traditional cell culture. Using cell studies that grow one or two cell types in culture either in a Petri dish or in Transwells cannot provide a healthy and controlled microenvironment for multiple cell types. Animal models do not always hold the same biological characteristics and relevance. While the organ-on-a-chip or microphysiological systems approach would target a degree of complexity and validity between the animal and cell culture approaches, chip models make cell retrieval nearly impossible without first lysing the cells. The approach of isolating the several cell types most important to biological processes through human-derived organoids is novel and potentially very powerful.

Validation

How do you validate the self-assembly of the ISCs and crosslinking of gels?

Identification of an epithelial monolayer with polarized nuclei (DAPI) and functional Goblet cells (Trefoil Fator 3) will be validated using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. Below are a few ways to further validate crypt morphology, stability, and cross-linking of the gel.

- Growth Factor Stability via FACS Expression Analysis

- Epithelial Cell Polarity via E-cadherin Staining

- Morphological Analysis via F-actin, Ki67, Muc5AC, nuclei DAPI Staining

- Assays to Ensure Reliability of Colony Formation

- Morphology and Quantification of Crypts via Confocal Z-Stacks with ImageJ Analysis

- Crosslinking of Hydrogels via Reflectance Imaging

- Use of Laminin Peptide Hydrogels for ISC Polarization

- Biomarkers of Homeostasis

Future Directions of Study

The addition of human intestinal microvasculature endothelial cells could dramatically extend the complexity of the system by incorporating an immune component via primary monocytes differentiated into macrophages and dendritic cells, and making the analysis of host-microbiome interactions possible.

Organoids derived from human tissue biopsies can be grown, frozen, and revived for multiple reuses, establishing a consistent bio-bank for reproducible experiments and potentially advancing personalized medicine. However, organoids are limited in that they lack the endothelial compartment, containing immune cells, which are pertinent to drug transport, microbiome development, pharmacokinetic analysis, and diease modeling.

Method for Isolating Gut Endothelium Cells

References

- Kasendra, Magdalena, Alessio Tovaglieri, Alexandra Sontheimer-Phelps, Sasan Jalili-Firoozinezhad, Amir Bein, Angeliki Chalkiadaki, William Scholl, et al. 2018. “Development of a Primary Human Small Intestine-on-a-Chip Using Biopsy-Derived Organoids.” Scientific Reports 8 (1): 2871. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-21201-7.

- Gillette, Brian M., Jacob A. Jensen, Meixin Wang, Jason Tchao, and Samuel K. Sia. 2010. “Dynamic Hydrogels: Switching of 3D Microenvironments Using Two-Component Naturally Derived Extracellular Matrices.” Advanced Materials 22 (6): 686–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.200902265.

- Gjorevski, Nikolce, Norman Sachs, Andrea Manfrin, Sonja Giger, Maiia E. Bragina, Paloma Ordóñez-Morán, Hans Clevers, and Matthias P. Lutolf. 2016. “Designer Matrices for Intestinal Stem Cell and Organoid Culture.” Nature 539 (7630): 560–64. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature20168.

- Haraldsen, G., J. Rugtveit, D. Kvale, T. Scholz, W. A. Muller, T. Hovig, and P. Brandtzaeg. 1995. “Isolation and Longterm Culture of Human Intestinal Microvascular Endothelial Cells.” Gut 37 (2): 225–34. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.37.2.225.

- Leushacke, M., and N. Barker. 2012. “Lgr5 and Lgr6 as Markers to Study Adult Stem Cell Roles in Self-Renewal and Cancer.” Oncogene 31 (25): 3009–22. https://doi.org/10.1038/onc.2011.479.

- Takahashi, Toshio, and Akira Shiraishi. 2020. “Stem Cell Signaling Pathways in the Small Intestine.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21 (6): 2032. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21062032.

- Thomas, Hugh. 2016. “Gut Endothelial Cells — Another Line of Defence.” Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 13 (1): 4–4. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2015.205.

- Wang, Fengchao, David Scoville, Xi C. He, Maxime M. Mahe, Andrew Box, John M. Perry, Nicholas R. Smith, et al. 2013. “Isolation and Characterization of Intestinal Stem Cells Based on Surface Marker Combinations and Colony-Formation Assay.” Gastroenterology 145 (2): 383-395.e21. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2013.04.050.

- Wells, Jerry M., Robert J. Brummer, Muriel Derrien, Thomas T. MacDonald, Freddy Troost, Patrice D. Cani, Vassilia Theodorou, et al. 2016. “Homeostasis of the Gut Barrier and Potential Biomarkers.” American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology 312 (3): G171–93. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpgi.00048.2015.

- “SnapShot: The Intestinal Crypt.” Elsevier Enhanced Reader. n.d. Accessed April 20, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.030.

- LeslieMar. 28, Mitch, 2019, and 1:00 Pm. 2019. “Closing in on a Century-Old Mystery, Scientists Are Figuring out What the Body’s ‘Tuft Cells’ Do.” Science, AAAS. March 28, 2019. https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2019/03/closing-century-old-mystery-scientists-are-figuring-out-what-body-s-tuft-cells-do.

- “The Immune Function of Tuft Cells at Gut Mucosal Surfaces and Beyond.” The Journal of Immunology. n.d. Accessed April 20, 2021. https://www.jimmunol.org/content/202/5/1321/tab-figures-data.